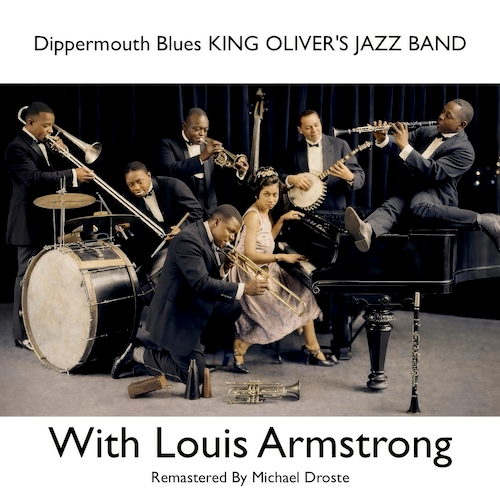

“Dippermouth Blues” stands as one of the foundational documents of early jazz, and Louis Armstrong’s performance with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band marks a hinge moment in American music—where collective improvisation begins to tilt toward the age of the soloist.

Recorded in 1923 in Richmond, Indiana, Dippermouth Blues captures Armstrong near the end of his apprenticeship under Joe “King” Oliver, his mentor, employer, and musical father figure. The tune itself is a classic New Orleans blues, built on a 12-bar structure, but what electrifies it is the conversation inside the band: cornet, clarinet, trombone, rhythm section—each voice interlocking with purpose, not chaos.

Armstrong plays second cornet, yet already bends the gravitational field around himself. His tone is firmer, more projecting, more rhythmically decisive than anyone else in the ensemble. While Oliver delivers the famous muted solo—using a metal derby mute to create the growling, vocalized sound that defined early jazz brass—Armstrong’s responses crackle with clarity and forward motion. You can hear the future arriving early.

The tune’s nickname comes from Oliver’s mute technique: the “dippermouth” sound, achieved by dipping the bell into the mute to create wah-like inflections. This was not novelty—it was language. Early jazz musicians treated the horn as a speaking instrument, mimicking the bends, cries, and textures of the human voice. Armstrong absorbed this concept deeply, later transforming it into his own open, ringing style that would redefine trumpet playing worldwide.

What makes Dippermouth Blues historically crucial is not just the sound, but the shift in musical thinking. King Oliver’s band represents the height of collective improvisation, where the group speaks as one organism. Armstrong, even here, hints at something else: rhythmic authority, melodic storytelling, and a sense that a single voice can carry narrative weight. Within two years, he would step fully into that role with the Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings.

The recording also documents the migration of New Orleans jazz into the broader American consciousness. Made for Gennett Records, it spread the sound of early jazz far beyond Chicago dance halls, influencing musicians who had never set foot in Louisiana.

Dippermouth Blues is not just an early jazz recording—it is a transmission moment. You can hear tradition being honored, challenged, and quietly surpassed. In those grooves, Louis Armstrong is still a sideman—but the future of jazz is already leaning toward his bell.